Microbatch topologies

In the tutorial, you saw an overview of microbatch topologies. Though broadly similar to using stream topologies, microbatch topologies have many important differences. They have significant additional capabilities for expressing computations, different performance characteristics, and simple exactly-once fault-tolerance semantics.

On this page, you’ll learn:

-

Additional computational capabilities supported by microbatch topologies

-

Phases of microbatch operation

-

How microbatch topologies achieve exactly-once semantics for PState updates regardless of failures and retries

-

Tuning options available for microbatch topologies

All examples on this page can be found in the rama-examples project.

Usage

Microbatch topologies process data that has accumulated on subscribed depots in one coordinated batch computation. There could be hundreds or thousands of unprocessed records on each depot partition that are processed together in a single microbatch. After finishing, a microbatch topology starts again with whatever data accumulated during the last microbatch. This is in contrast to stream topologies which process depot records independently and concurrently as they are appended.

Here’s an example of a microbatch topology:

public class ExampleMicrobatchTopologyModule implements RamaModule {

@Override

public void define(Setup setup, Topologies topologies) {

setup.declareDepot("*keyPairsDepot", Depot.hashBy(Ops.FIRST));

setup.declareDepot("*numbersDepot", Depot.random());

MicrobatchTopology mb = topologies.microbatch("mb");

mb.pstate(

"$$keyPairCounts",

PState.mapSchema(

String.class,

PState.mapSchema(String.class, Long.class).subindexed()));

mb.pstate("$$globalSum", Long.class).global().initialValue(0L);

mb.source("*keyPairsDepot").out("*microbatch")

.explodeMicrobatch("*microbatch").out("*tuple")

.each(Ops.EXPAND, "*tuple").out("*k", "*k2")

.compoundAgg("$$keyPairCounts", CompoundAgg.map("*k", CompoundAgg.map("*k2", Agg.count())));

mb.source("*numbersDepot").out("*microbatch")

.batchBlock(

Block.explodeMicrobatch("*microbatch").out("*v")

.globalPartition()

.agg("$$globalSum", Agg.sum("*v")));

}

public static void main(String[] args) throws Exception {

try(InProcessCluster cluster = InProcessCluster.create()) {

RamaModule module = new ExampleMicrobatchTopologyModule();

cluster.launchModule(module, new LaunchConfig(4, 4));

String moduleName = module.getClass().getName();

Depot keyPairsDepot = cluster.clusterDepot(moduleName, "*keyPairsDepot");

Depot numbersDepot = cluster.clusterDepot(moduleName, "*numbersDepot");

PState keyPairCounts = cluster.clusterPState(moduleName, "$$keyPairCounts");

PState globalSum = cluster.clusterPState(moduleName, "$$globalSum");

numbersDepot.append(1);

numbersDepot.append(3);

numbersDepot.append(7);

keyPairsDepot.append(Arrays.asList("a", "b"));

keyPairsDepot.append(Arrays.asList("a", "b"));

keyPairsDepot.append(Arrays.asList("a", "c"));

keyPairsDepot.append(Arrays.asList("x", "y"));

keyPairsDepot.append(Arrays.asList("x", "y"));

keyPairsDepot.append(Arrays.asList("x", "y"));

keyPairsDepot.append(Arrays.asList("x", "z"));

cluster.waitForMicrobatchProcessedCount(moduleName, "mb", 10);

System.out.println("Global sum: " + globalSum.selectOne(Path.stay()));

System.out.println("Counts for 'a': " + keyPairCounts.select(Path.key("a").all()));

System.out.println("Counts for 'x': " + keyPairCounts.select(Path.key("x").all()));

}

}

}Once again, the main method demonstrates what it would be like using this module once deployed on a cluster. Just like stream topologies, microbatch topologies can declare as many PStates and consume from as many depots as they wish. Although this example does not do so, when you have multiple source blocks on a topology it’s common for them to modify the same PStates.

In microbatch topologies, depot sources emit an object representing the batch of data for this microbatch across all that depot’s partitions. This object can only be used in conjunction with explodeMicrobatch, which emits each piece of data across all partitions. The code after explodeMicrobatch runs on all partitions of the depot that had data for the microbatch.

The entire dataflow API is available in microbatch topologies. Unlike stream topologies, microbatch topologies can take advantage of Rama’s batch computation capabilities with batchBlock. Batch blocks open up a huge amount of power, including two-phase aggregation, joins, and temporary PStates. See this section for details on batch blocks.

All the dataflow constructs are composable with one another. You can use partitioners within conditionals or batch blocks, and you can use batch blocks within loops. You can even mix batch blocks with regular dataflow code in the same source block, although this isn’t common. The only restriction with batch blocks is they must be initiated from task 0 (always the starting task at the beginning of a microbatch source block). You can string multiple batch blocks together since the code after a batch block runs on task 0.

This example uses "*keyPairsDepot" to count each pair of keys. It uses "*numbersDepot" to compute the sum of all the numbers. The batch block in that source block takes advantage of two-phase aggregation, which makes that global sum scalable and extremely performant.

Running main prints:

Global sum: 11

Counts for 'a': [["b" 2] ["c" 1]]

Counts for 'x': [["y" 3] ["z" 1]]Microbatch topologies do not integrate with depot appends because they run asynchronously to the appends. In tests, you utilize waitForMicrobatchProcessedCount to know when your microbatch topology has processed all the data you appended. In this case, since ten records were appended, it uses waitForMicrobatchProcessedCount to wait for ten records to be processed.

Multi-source

As of Rama 1.2.0, topologies can consume from the same depot multiple times. Multi-source for microbatch topologies works the same as for stream topologies, and this feature is documented in this section.

Operation and fault-tolerance

Microbatch topologies are designed for high throughput and exactly-once fault-tolerance semantics. Let’s take a look at a broad overview of the implementation of microbatch topologies to see how this is achieved. Though you don’t need to understand the implementation to use them effectively, this information will help you understand the telemetry for microbatch topologies in the Cluster UI.

A microbatch topology is controlled by a "runner" on the task 0 leader. This runner shares the task 0 thread with all other events running on that thread (topology events, PState reads, etc.). Like everything else in Rama, this runner does not block the task thread but instead runs as a series of asynchronous events.

The runner launches a microbatch, detects when it finishes processing, and coordinates when changes to PStates are made visible to clients and other topologies. Once this procedure finishes successfully, it starts again with the next set of unprocessed data that has accumulated on depots. You can think of the runner as an asynchronous while(true) loop where each iteration of the loop processes a single microbatch.

A single iteration of the microbatch runner is called a "microbatch attempt". A microbatch attempt is identified by a microbatch ID and version. If a microbatch fails (e.g. an exception in the topology, a leadership change during processing, or a timeout), it is re-attempted with the same microbatch ID and an incremented version. Each attempt for the same microbatch ID processes the exact same set of data from the depots, even if more data has accumulated on the depots since the first attempt. Additionally, each microbatch attempt starts with the PStates at exactly their state after the previous microbatch ID. The microbatch ID and version are stored on an internal PState dedicated to the topology with a name of the form "$$__microbatcher-state-<topologyId>".

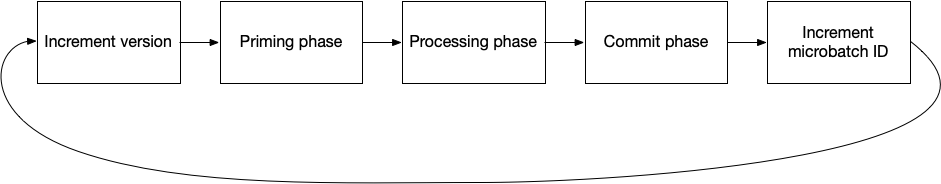

A microbatch topology executes in three phases: priming phase, processing phase, and commit phase. Each phase completes before moving on to the next phase. The version is incremented at the start, and the microbatch ID is incremented at the end. All of these are coordinated by the task 0 runner. Here’s a diagram of how microbatch topologies work:

The priming phase runs an event on every task to prepare them for the upcoming microbatch. It clears internal buffers used for joins and aggregations, clears temporary PStates, and resets every user PState (e.g. "$$keyPairCounts" in the above example) to the state at the end of the previous microbatch ID. User PStates have separate internal and external views which are managed separately. This reset only affects the internal view, and topology code always operates on the internal views of user PStates.

The processing phase runs your topology code. The first time explodeMicrobatch is called on a depot source for a microbatch ID, the range of data to read per partition for that microbatch ID is written and replicated. The max amount of data to read per partition is configurable by the dynamic option depot.microbatch.max.records.

After the processing phase finishes, all PState updates have been applied by the topology. The commit phase checkpoints the internal PStates and marks them with the microbatch ID / version of the microbatch. This checkpointing process predominantly involves making hard links on disk. The latest versions for the last two microbatch IDs are always kept, ensuring the microbatch can restart with the state from the last microbatch ID if any worker involved in the commit phase were to fail. The commit phase also replicates all changes from the microbatch to followers. After all PStates on a task have been checkpointed and replicated, their external versions are updated to what was just checkpointed. This is when changes are made visible to clients and other topologies. This means all changes to all PStates on a task in a microbatch become visible at the exact same time (though changes on different tasks may become visible at slightly different times).

Because microbatch topologies always start from the state of the last microbatch ID, and because they always process the exact same set of depot records, they have exactly-once semantics for PState updates regardless of failures in any of the phases.

A microbatch topology is not necessarily deterministic, however. That depends entirely on the topology code. If you use shufflePartition, random numbers, or query mirror PStates in your topology, the results after a retry could be different than the previous version for the same microbatch ID. Importantly, the resulting PStates still do represent the processing of each depot record exactly one time. When a new version of a PState is computed for the same microbatch ID, the new version replaces the old version in the external view of the PState.

If you do depot appends as part of your microbatch topology to either the same module or other modules, those currently do not have exactly-once semantics in the face of failures and retries. However, this is on our roadmap.

"Start from" options

Like stream topologies, you can configure a microbatch topology to begin processing depots from some point in the past. By default, they will start from the end and only process records appended after the topology started. These options only have an effect the first time the microbatch topology encounters that depot, either on a module launch or by adding a new depot source in a module update.

Here are examples of all the different options you can configure:

mb.source("*depot", MicrobatchSourceOptions.startFromBeginning())

mb.source("*depot2", MicrobatchSourceOptions.startFromOffsetAfterTimestamp(107740800000))

mb.source("*depot3", MicrobatchSourceOptions.startFromOffsetAgo(10000, OffsetAgo.RECORDS))

mb.source("*depot4", MicrobatchSourceOptions.startFromOffsetAgo(15, OffsetAgo.DAYS))See this section for a description of what these do.

There are no other options besides these on MicrobatchSourceOptions. Unlike stream topologies, there’s nothing you need to worry about with regards to retry modes and fault-tolerance since microbatch topologies always have exactly-once semantics.

Tuning options

There are a variety of dynamic options available for microbatch topologies. Dynamic options can be edited from the Cluster UI and take effect immediately. The relevant dynamic options are:

-

depot.microbatch.max.records: This is the maximum number of records to read per depot partition for a microbatch. Higher numbers allow a microbatch to benefit from increased batching across the board, but too high a number risks running out of memory during the processing phase. -

depot.max.fetch: This is the maximum number of depot records to fetch from a partition at a time in a single event. Bigger fetches take longer and will thereby utilize the task thread for longer. This should be less than or equal todepot.microbatch.max.records. Filling the data read for a partition up todepot.microbatch.max.recordswill span some number of events each fetching a maximum ofdepot.max.fetchrecords at a time. -

topology.microbatch.phase.timeout.seconds: This is the timeout for each phase of a microbatch. If a phase takes longer than this, it will fail and the microbatch will retry from the start. -

topology.microbatch.empty.sleep.time.millis: If a microbatch does not process any records, the runner will sleep for this amount of time before launching the next microbatch. This prevents microbatches from running in a tight loop using large amounts of CPU across the cluster when the rate of incoming data is low. -

topology.microbatch.pstate.flush.path.count: This is the rate at which writes to PStates are flushed to disk. A higher number will get improved write performance via increased batching, but since writes happen in a task thread it also risks utilizing a task thread for too long. -

worker.combined.transfer.limit: Microbatch topologies use this value to determine how many outgoing events to package together into a single network message. Higher values get improved throughput from increased batching, but too high a number risks delays at the network level. Since each worker only listens on one port, a single incoming message that’s too large will cause delays to all traffic coming to that worker (like PState client reads). -

topology.combiner.limit: For combiners that require flushing, this determines the frequency at which they flush in terms of number of aggregations. Note that most combiners do not require flushing so it’s unlikely you’ll need to edit this. -

topology.microbatch.ack.branching.factor: To scalably detect completion of the processing phase, a microbatch topology implements a hierarchical acking algorithm. Tasks are arranged into a tree using this branching factor, with the root task being task 0. Tasks funnel information about event completion to their parent task, and event completion information is combined together as it works its way up the tree. Tasks forward completion information to their parent when they haven’t received any new completion information in a fixed amount of time. -

topology.microbatch.ack.delay.base.millis: This determines the minimum amount of time to wait for new completion information in the hierarchical acking algorithm. If new completion information is received in this time window, the wait starts over again. -

topology.microbatch.ack.delay.step.millis: This increases the amount of time to wait for completion information for each level of the tree. As a task gets closer to task 0, it waits longer. This helps even out the amount of load incurred by each task in the acking tree.

Summary

Updating PStates with microbatch topologies is different than how databases are normally interacted with. For decades the predominant pattern has been to do reads and writes to databases from an application layer, which is essentially like stream processing without the structured framework for it.

Unless you require millisecond-level update latency for your PStates, you should generally prefer microbatch topologies. They have higher throughput and simpler fault-tolerance semantics than stream topologies. Their additional computational capabilities through batch blocks are also very significant.