Replication

All data in Rama is replicated across a configurable number of nodes. This includes all depot and PState data as well as internal state like microbatch and stream topology progress. Replication provides fault-tolerance to losing machines, disks, or other components by enabling automatic failover to other nodes.

Replication in Rama happens completely behind-the-scenes. All you have to do as a user is configure the amount of replication you desire. Although you don’t have to use replication, we highly recommend you do. All machines eventually fail, and the larger your cluster the more frequent the failures will be.

Although you don’t need to understand replication to use Rama, understanding how replication works at a high level can be helpful when looking at logs or diagnosing issues. On this page, you’ll learn:

-

How data is replicated in Rama

-

The leader and follower roles for task threads

-

What are the ISR and OSR

-

How Rama provides strong guarantees on data integrity

-

Configuring replication with the "replication factor" and "min-ISR" settings

-

How lagging followers catch up using near-horizon or far-horizon catchup

-

How replication uses the Metastore

-

Replication telemetry available in the Cluster UI

How data is replicated

The replication factor configuration tells Rama how many times each piece of data should be stored. Replication happens at the task group level, so task groups are duplicated around the cluster according to the replication factor. Rama first decides which tasks to assign to each task group and then decides how to distribute each replica of each task group to workers. Duplicate task groups are always assigned to workers on different nodes.

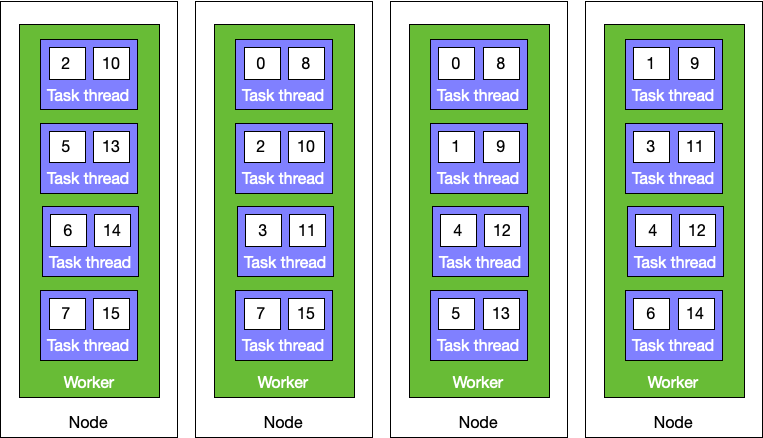

The number of worker processes launched for a module is equal to the number of workers configured for the module multiplied by the replication factor. So if you launched a module with eight workers and a replication factor of three, there would be 24 worker processes launched total. Here’s a visualization of what an assignment could look like for sixteen tasks, eight threads, two workers, and a replication factor of two:

As you can see here, each task group is duplicated two times and each worker contains a potentially unique distribution of task groups. One of the task threads for each task group is designated the leader and the rest are designated followers. How they take on those roles will be described more in the next section.

The leader is responsible for performing all work for each of the tasks in its task group: running ETL code, updating PStates, appending to depots, and serving PState client queries. The leader synchronizes any changes to PStates, depots, or other internal state to its followers. If a leader dies for any reason, any follower that is "in sync" (more on this later) can take over as the new leader.

At the center of the replication process is the "replog", short for "replication log". The replog is an on-disk log structure that contains "replog entries". A replog entry represents any change to any object on any task within the task group. The replog captures all the changes that happen in a task group in the exact order in which they happened. The replog assigns each entry a sequential "offset", which refers to its position in the log.

Here are some examples of replog entries:

-

Depot append

-

PState updates for a stream topology batch, contains map from PState name to list of paths

-

Update to internal stream topology progress PState

-

Recording microbatch ID / version for microbatch runner on internal PState on task 0

When a leader creates a new replog entry (e.g. at the end of a stream topology batch), it replicates that entry to followers before making the changes from that entry visible. Until sufficient followers have confirmed receipt of the entry into their replogs, those changes will not be visible to any clients (such as foreign PState clients). This provides the guarantee that when data is visible for a depot or PState, it will still be visible if the current leader fails and a new leader takes over.

The first step to replicating a replog entry is to forward that entry to all followers. There’s some intricacy as to which followers are eligible to receive an entry at any given moment: a follower has to be "in sync" or "close to in sync" to qualify. A follower that’s too far behind instead performs far-horizon catchup, which will be explained more later. When a follower receives replog entries from a leader, it sends a message back with the maximum replog offset it has.

The leader tracks a value called the apply offset which is the latest replog entry that can be applied. Applying a replog entry performs its changes to any depots, PStates, or internal states and makes them visible. The apply offset is advanced when sufficient followers have confirmed they have received and appended that replog entry offset to their replog. Leaders inform their followers of updates to the apply offset so followers can apply their replog entries too.

In summary, a leader sends messages to its followers containing new replog entries and/or updates to the apply offset. A follower sends messages to its leader with the maximum replog offset it has.

There’s a lot of detail as to how all this implemented. These include how replog appends and forwarding batch work to improve performance and the exact situations that leaders and followers send messages. This detail isn’t important for understanding the semantics of replication, so we’ll stay at a high-level on this page.

Leadership balancing

Leaders perform all ETL processing, foreign PState client reads, depot appends, replog entry creation, and other work for a task group. Followers, on the other hand, just receive and apply replog entries. So the amount of work a leader task thread does is significantly more than a follower task thread. For this reason, Rama takes care to evenly distributed leaders around a cluster to make good use of resources.

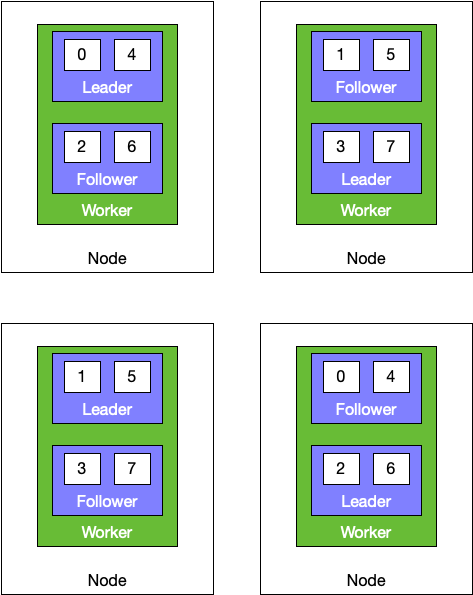

Here’s an example of how leaders might be distributed for a module across nodes and workers:

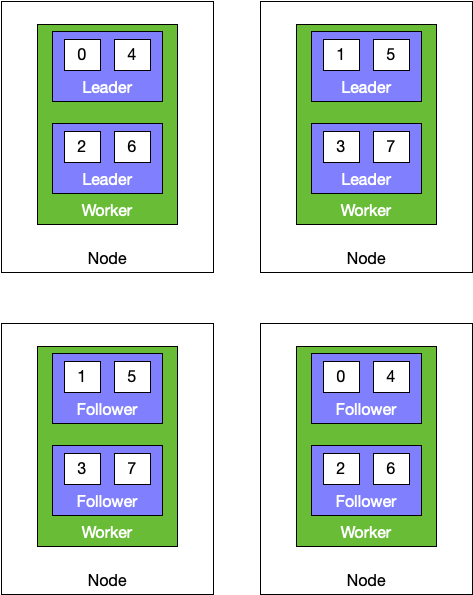

This module has eight tasks, four threads, two workers, four nodes, and a replication factor of two. Because every node has an equal number of leaders, the distribution of processing is balanced and resources are being used efficiently. Compare this to an unbalanced distribution like this:

In this assignment, resource usage will be heavily skewed towards the nodes running all the leaders. Things like foreign PState queries are only served by half the cluster, greatly limiting the maximum throughput this cluster can handle.

Rama constantly monitors the cluster to keep the leadership distribution as close to the first image as possible. When disks fail, nodes go down, or there are other failures leadership changes will happen. Critically, Rama always balances leadership as best as possible according to what resources are currently available.

The Conductor runs a routine called "leadership balancing". In the Cluster UI, you’ll sometimes see the state of modules change to [:leadership-balancing] for a brief time. This routine checks the current locations of leaders and whether a more balanced configuration is possible. If so, Rama determines the minimal number of leadership switches to get the cluster to that balanced state. Rama informs those leaders to resign, and those leaders then undergo a coordinated procedure to hand off leadership to a more optimally located follower that’s eligible to be a leader.

ISR and OSR

Earlier we mentioned the concepts of sufficient followers receiving replog entries and followers being eligible to become leaders. These both relate to critical concepts within replication called the ISR and OSR.

ISR stands for "in-sync replicas", and OSR stands for "out-of-sync replicas". Every follower is part of either the ISR or OSR, and a leader is always part of the ISR. A follower is part of the ISR if it has all the data and replog entries necessary to become a leader. Otherwise, it’s part of the OSR. A follower in the ISR hasn’t necessarily applied all its replog entries yet, but if it suddenly becomes leader it will apply them before serving any reads. This property of the ISR guarantees that any data that is currently visible on a leader will still be visible on any subsequent leader.

A leader manages which followers are part of the ISR and OSR. At the core of how a leader operates is how it handles followers failing to keep up. This brings up another core configuration of replication called the "min-ISR". The min-ISR is the minimum number of replicas (leader and follower task threads) that must have a replog entry before it can be applied. The min-ISR defaults to one less than the replication factor and can be edited at any time via a dynamic option.

When the leader looks to apply the next unapplied replog entry, it first checks if every member of the ISR has confirmed receipt of the entry. If not, it starts a stall timer. This timer can be adjusted through the dynamic option replication.max.time.lag.millis. Members of the ISR that have not reported receipt of that entry have at most that amount of time to report that entry. If the stall timer expires, the leader decides whether to move any ISR members to the OSR.

If moving the stalling ISR members to the OSR would keep the ISR at least min-ISR in size, the leader moves them and then applies the replog entry. The ordering here is critical: if the leader were to apply the replog entry before moving the stalling ISR members, a sudden leader switch to one of the stalling ISR members could lead to visible data from the applied replog entry disappearing. Since instead the leader moves the stalling ISR members first, it’s impossible for them to take leadership after the replog entry is applied since they’re in the OSR.

If the leader can’t move the stalling ISR members without violating min-ISR, then it neither applies the replog entry nor moves the ISR members. Since it requires min-ISR to apply the replog entry, it can’t apply it. And since the replog entry wasn’t applied, the stalling ISR members are still in the ISR since they have all data and replog entries visible on the leader. In this situation, the leader is stalled because it is unable to make any progress on applying replog entries. The stall will remain until enough stalling ISR members become functional again.

In this situation, all depot appends and PState updates to that task group will fail. Stream processing that goes through that task group will fail. Any task group being stalled in the module will cause all microbatch topologies in the module to continuously fail since microbatching operates across all task groups in a coordinated series of operations. So a task group being stalled is a bad situation and one you don’t want to occur.

The replication factor and min-ISR settings you choose are a tradeoff between resource usage, the likelihood of a stall, and data integrity. The higher your replication factor and/or min-ISR, the less likely you’ll lose all your replicas and encounter data loss. But the higher your min-ISR relative to your replication factor, the more likely you’ll have a stall. For most use cases we recommend a replication factor of three and a min-ISR of two.

Configuring replication

The replication factor for a module instance is configured on launch via a flag on the CLI command. For example:

rama deploy \

--action launch \

--jar target/my-application.jar \

--module com.mycompany.MyModule \

--tasks 64 \

--threads 16 \

--workers 8 \

--replicationFactor 3The replication factor can also be increased or decreased when scaling a module. For example:

rama scaleExecutors \

--module com.mycompany.MyModule \

--threads 90 \

--workers 30 \

--replicationFactor 3The min-ISR setting, on the other hand, is a dynamic option that can be changed at any time. This option is typically set on the module instance page of the Cluster UI. The dynamic option is named replication.min.isr.

When this dynamic option is unset, the module will infer the min-ISR setting as one less than the replication factor. If it’s set to a value less than one, it will be interpreted internally as one. If it’s set to a value greater than the replication factor, it will be interpreted internally as equal to the replication factor.

Leader epochs

Let’s take a look at some more details of how replication works, starting with leader epochs. In no way do you need to understand leader epochs to master using Rama, but it’s a core concept within the replication implementation.

The leader epoch is a number that increases by one every time a new leader takes over a task group. The leader epoch enables a new leader to coordinate the transition of leadership while maintaining the guarantee that all applied replog entries on the former leader are still visible on the new leader.

Any replog entry that wasn’t applied on the former leader can safely be dropped, and this is a key insight that will be used during a leadership transition. There’s no data loss when doing this since the high level operation (e.g. depot append or PState update in a topology) never succeeded and will retry if appropriate. A replication failure due to a leader switch in a stream topology will cause the topology to retry the depot record from scratch. A replication failure during a microbatch topology will cause the entire microbatch to retry, and since microbatch topologies have exactly-once semantics the result of processing will be as if there were no failures at all.

On a leader switch, the other ISR members may have inconsistent replogs. The former leader may have succeeded in sending some replog entries to some followers but not to others. The new leader doesn’t know which of its unapplied replog entries may have been applied by the former leader because it doesn’t know the state of the other followers. So it doesn’t know if the leader reached min-ISR for any of those entries. But it knows it has any replog entries that were applied by the former leader because that’s the precondition for being in the ISR.

To make sure all members of the ISR are consistent, the new leader treats its replog as authoritative. It informs its followers of the new epoch and which offsets correspond to which epochs in its replog. Followers then drop any replog entries that are inconsistent with the leader’s replog. The leader will then send all entries needed by a follower to become fully consistent.

The new leader must apply all entries that were in its replog on the leader switch before performing any topology processing or serving reads, because any or all of the entries could have been applied on the former leader. Once it knows each of those has reached all ISR members, and the ISR is at least min-ISR in size, it applies them and begins topology processing and serving reads.

Near-horizon and far-horizon catchup

A follower in the OSR works to get back into the ISR as soon as possible. How it achieve this depends on how out-of-sync it is with its leader.

The leader is a moving target while a follower is catching up. As long as the ISR has at-least min-ISR members, the leader will continue adding and applying replog entries. Catchup works because the work a follower does is less than a leader for a variety of reasons: the follower doesn’t serve any PState reads, the follower doesn’t execute any topology code, and the follower is able to batch operations more than the leader.

A follower who can become in-sync by applying a small number of replog entries performs "near-horizon catchup". Near-horizon catchup works just like regular replication by receiving replog entries from the leader and reporting received offsets back. Once the leader detects a follower has all the replog entries necessary to be in the ISR, it puts that follower back into the ISR.

The maximum number of replog entries a follower can be behind to perform near-horizon catchup is governed by the replication.max.near.sync.message.lag dynamic option. When a follower is further behind than that, the system assumes it will be more efficient to transfer the files underlying PStates, depots, and other internal state directly than to rebuild them incrementally by applying replog entries. Additionally, it’s undesirable to keep replog entries forever, so bounding the number of replog entries that can be used for near-horizon catchup lets replog entries beyond that point be deleted. This frees up that disk space.

Far-horizon catchup is the mechanism by which OSR members become in-sync with leaders when they are too far behind the leader’s replog. It works by transferring files directly from the leader for all PStates, depots, and other internal state over a series of "transfer rounds" until within range of the leader’s replog to finish with near-horizon catchup. Each transfer round transfers the files the follower does not have from the leader. The first transfer round will include everything, and subsequent transfer rounds will only contain the new files that accumulated during the prior transfer round. Because the files underlying depots and PStates are generally immutable, the transfer rounds are expected to get faster and faster.

The dynamic option replication.far.horizon.min.transfer.rounds governs how many transfer rounds are performed. Each object being transferred is handled independently, and each keeps doing transfer rounds until all of them have performed at least the number of transfer rounds specified by that dynamic option. Because depots and PStates can vary in size a great deal, a smaller object will perform many more transfer rounds than a larger object.

Currently, Rama stops performing transfer rounds once that condition is met. If it’s not within range of the replog at that point, far-horizon restarts from scratch and a log message containing the following will be printed in the follower’s worker log:

Leader reported missing entries from our replog while in far-horizon catchup.

Increasing the dynamic option 'replication.far.horizon.min.transfer.rounds' may

help far-horizon get within range of leader's replog.As the log message suggests, we recommend increasing that dynamic option if this were to happen. However, with the default settings this is extremely unlikely. We also have it on our roadmap to change Rama to keep doing transfer rounds until it is definitively within range of the replog, which will remove the need for this dynamic option.

How replication uses the Metastore

Rama’s Metastore is implemented using Zookeeper and is used to store cluster metadata. Quite a bit of that cluster metadata is for replication.

Critically, no data ever goes through the Metastore (such as replog entries). That would be extremely inefficient. Here are the things replication does use the Metastore for:

-

Leadership election

-

Tracking the ISR and OSR for each task group

-

Tracking the leader epoch for each task group

-

Coordinating leader resignation

The Metastore is also used for many other things, such as by the Conductor to let Supervisors know what workers are assigned to them, coordinating module updates, and other tasks. In all cases only metadata such as coordination information is stored on the Metastore.

Replication telemetry in the Cluster UI

Let’s take a look at the replication telemetry available in the Cluster UI. These metrics can be viewed aggregated for the module as a whole on the module instance page, and they can be viewed for each worker individually on the worker pages.

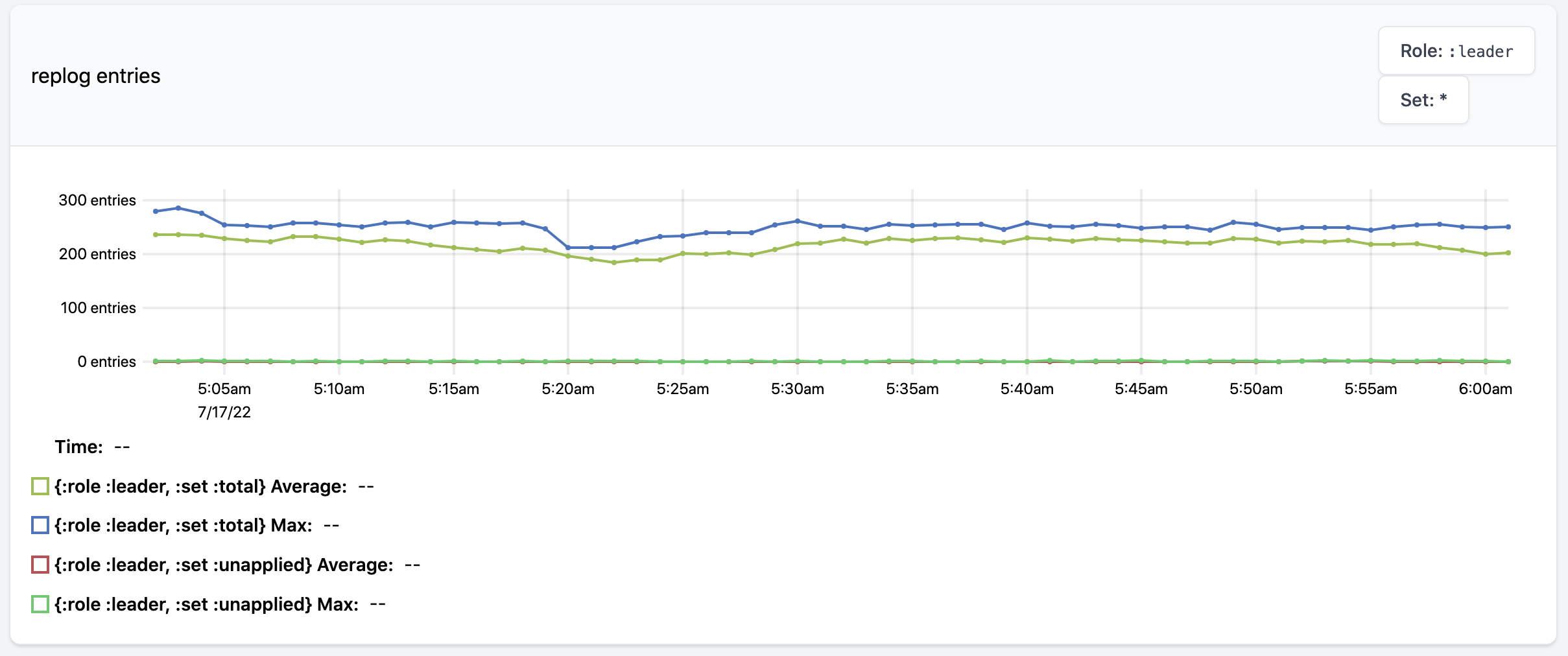

Here’s what each of the metrics looks like:

The replog entries metric shows the average and maximum size of replogs across all task threads in question. For a module this measures across all task threads, and for a worker this measures across all task threads in that worker. One dropdown on the top-right lets you look at leaders and ISR followers separately, and the other dropdown lets you look at replog size or the number of unapplied replog entries on task threads. In this example every task thread is at full ISR, so the sizes of the replogs are small since they’re able to be cleaned up frequently.

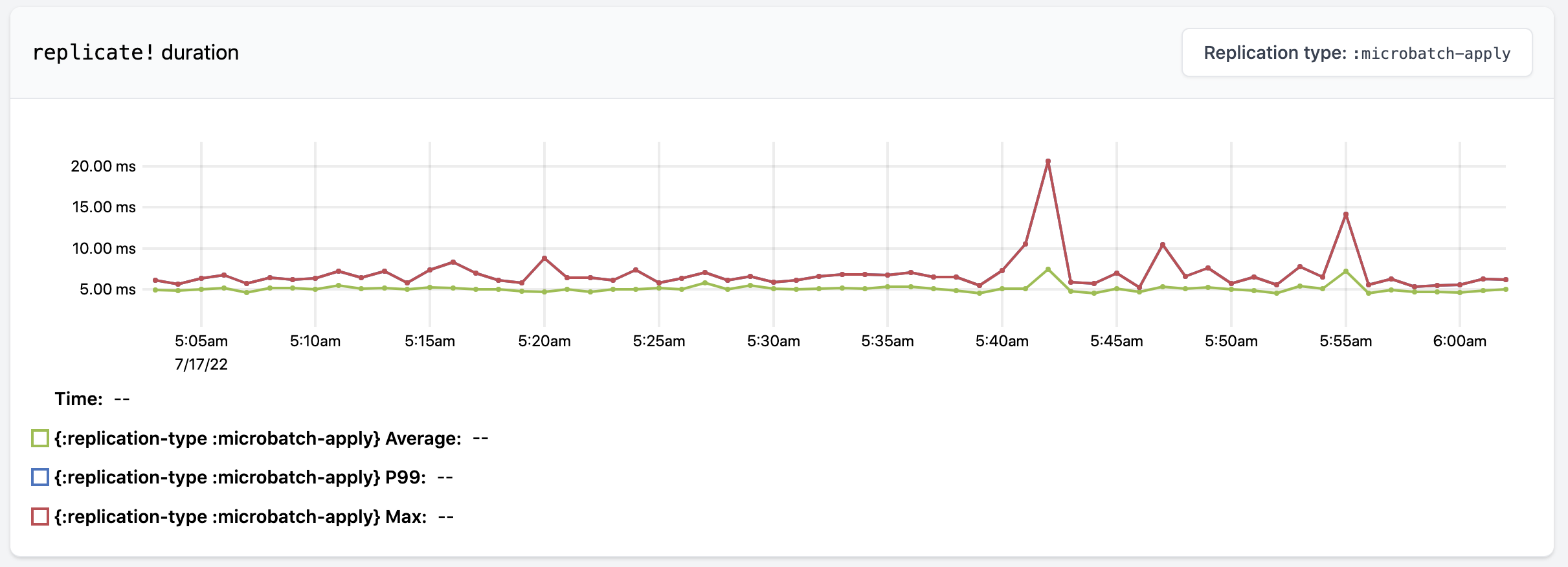

The next three metrics are about the replicate! operation. replicate! is the internal operation within Rama that performs replication for a replog entry. The replicate! duration metric measures the time from creating the replog entry to it being applied by the leader. This includes the time it takes to forward the entries and receive confirmation of those entries being received by followers. Through the dropdown on the top-right you can look at the durations based on the kind of replog entry being replicated. Similar to replicate! duration, the replicate! throughput metric shows the number of times replicate! is called for each replog entry type.

replicate! failures is a time-series of the number of replication failures on each task thread, such as when a task thread cannot replicate to at least min-ISR replicas. When a cluster is healthy, this chart will be empty.

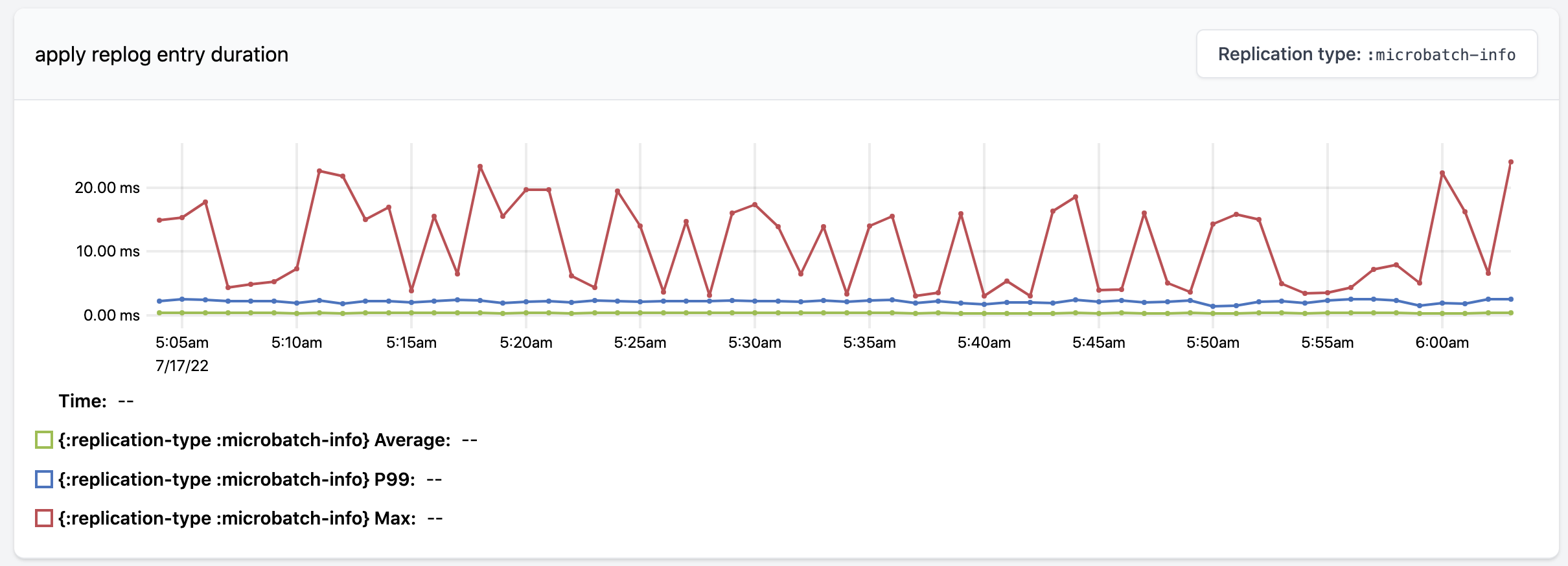

apply duration shows the time it takes to apply a replog entry, which is the final part of the replication process. Once again you can look at the differences across replog entry types through the dropdown on the top-right.

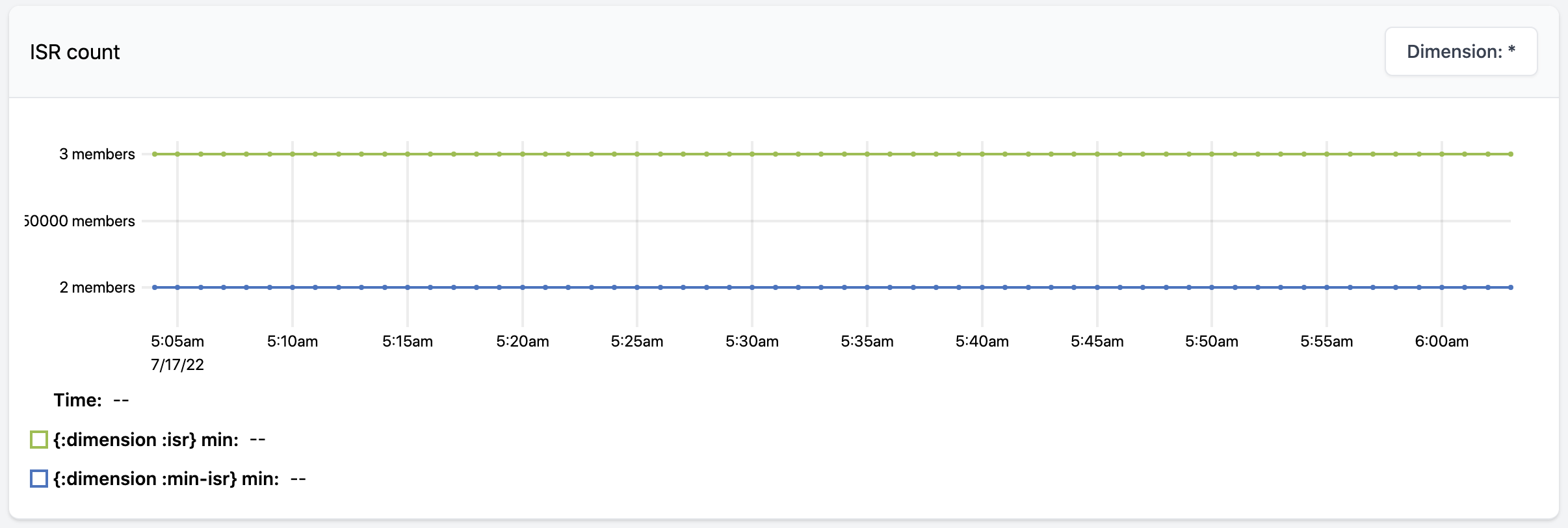

Lastly, ISR count shows the worst task group at any given moment in terms of ISR status. Each sample on the graph shows the min-ISR setting at that time and the size of the smallest ISR set across all task groups in question. This example shows a healthy module with a min-ISR of two where every task group’s ISR size is equal to the replication factor of the module.

Summary

As you’ve seen on this page, a great deal of Rama’s implementation is dedicated to replication. The nice thing about replication is it happens completely behind the scenes. As a user, you only need to specify the replication factor and min-ISR setting to manage the tradeoffs between data integrity, fault-tolerance, and availability appropriate for your application.